Hunter syndrome, also called mucopolysaccharidosis type II, is a rare genetic disease that almost always affects boys.

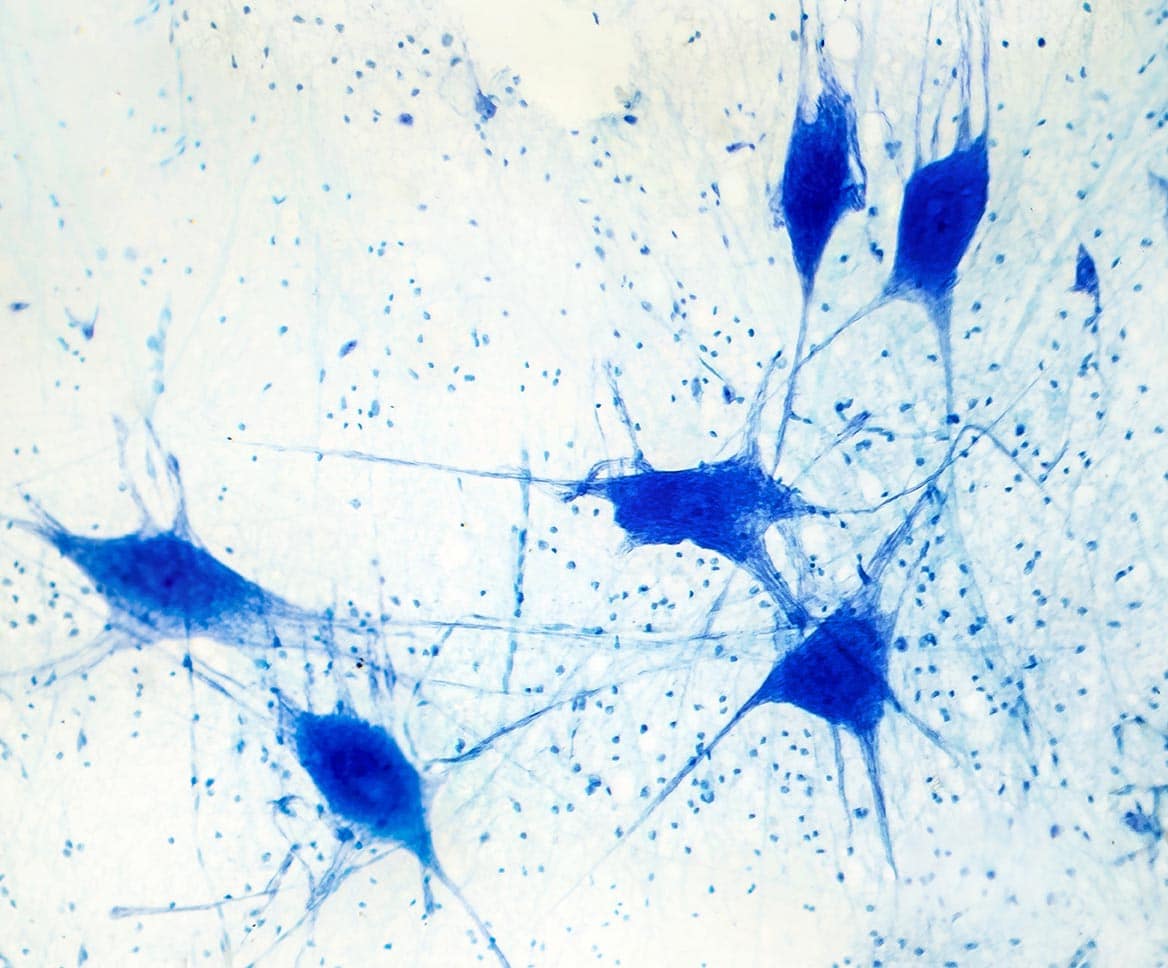

Caused by a faulty gene, children born with the condition can experience a wide range of symptoms affecting many tissues and organs, including their brain, liver, lungs, bones, eyes, skin and heart.

Danny’s story

Having had a history of developmental delay, Danny was diagnosed with Hunter syndrome when he was three years old. Subsequent tests found he had the most severe form of the disease and the worst possible outlook, because he was completely missing a gene in his DNA.

The gene encodes an enzyme which breaks down complex sugars, and if you don’t have the gene to make the enzyme, these sugars build up and affect many systems in the body.

Danny’s family are painfully aware that time with their youngest son will be cruelly cut short by this rare disease which has no cure and limited treatment options.

“Danny lives in the moment and enjoys whatever he has,” said Danny’s mum, Sally.

This ‘in the moment’ outlook is one that Sally herself tries hard to adopt. Time with Danny, now nine, is incredibly precious.

Life has got calmer lately but for the saddest of reasons. Danny is now losing skills he previously had. He no longer speaks and will gradually become more reliant on his wheelchair.

There is an urgent need to develop new treatments for boys with this devastating condition – especially those that can reduce brain symptoms.

“I’d love to have my little trouble back in full force, because I know what this calm after the storm is leading to. Each new research development brings real hope for families in the future,” says Sally.

Can gene therapy help?

Together with children’s charity Action Medical Research, we are funding a lab project at the University of Manchester to find out if an innovative stem cell gene therapy can help children with Hunter syndrome.

The team will find out if they can alter the patient’s own bone marrow cells to produce the missing enzyme and stop the sugars building up, and also tag the enzyme so it can cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain to do the same.

If the project is successful, it could pave the way for a future clinical trial in boys with Hunter syndrome.

At the prospect of a new treatment which could one day transform the outlook for boys with Hunter Syndrome, Sally says: “Unfortunately, this research will come too late for our family and one day we will lose our beautiful boy to Hunter syndrome. But any new hope is worth fighting for. So that families in the future don’t have to feel that the bottom is dropping out of their world.”

Find out more about LifeArc’s funding for rare disease research.