A young actor battled a rare liver disease through college and drama school before getting fit enough to start a successful career.

Actor Ashley Hudson from Norfolk lives with primary sclerosing cholangitis or PSC. It is a rare liver disease where the body attacks itself, causing inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts and liver, and affects around 3,600 people of all ages in the UK. There is no cure, but a range of treatments are available that can help control symptoms.

Many people will ultimately need a life-saving liver transplant. Although a very rare disease, PSC accounts for around one in 10 of all liver transplants in the UK and is the main reason why people have liver transplants in several European countries.

Battling the rare inflammatory bowel disease

Ashley was diagnosed with PSC at the age of 13. He missed a lot of school during his teenage years, as he was so unwell.

“I was a very energetic child – enjoying lots of hobbies, such as racing carts and playing football,” he says. “But that all stopped when I became ill – it affected my mental health, I didn’t have much strength and felt very tired all the time.”

Ashley first noticed something was wrong when the smell of food started to make him feel sick – and he also became pale and jaundiced.

Life-changing liver transplant

After his diagnosis, Ashley received different medications to try and control the symptoms of PSC and inflammatory bowel disease. At 23, he received a life-changing liver transplant after potentially cancerous nodules were discovered in his liver.

“After my transplant, I felt so different,” he says. “While it’s not a cure, I now have 80 percent more energy, my body doesn’t ache as much and my mind is much clearer.”

Since his transplant, Ashley has performed on theatre tours and appeared in films and music videos. He still goes for hospital appointments to check up on his condition and has regular colonoscopies to screen for signs of bowel cancer.

Faecal transplant – a promising option?

Scientists have discovered the microbes living in the gut of people with PSC are different to those in people without PSC. This gut microbe imbalance is thought to play a key role in driving development of PSC.

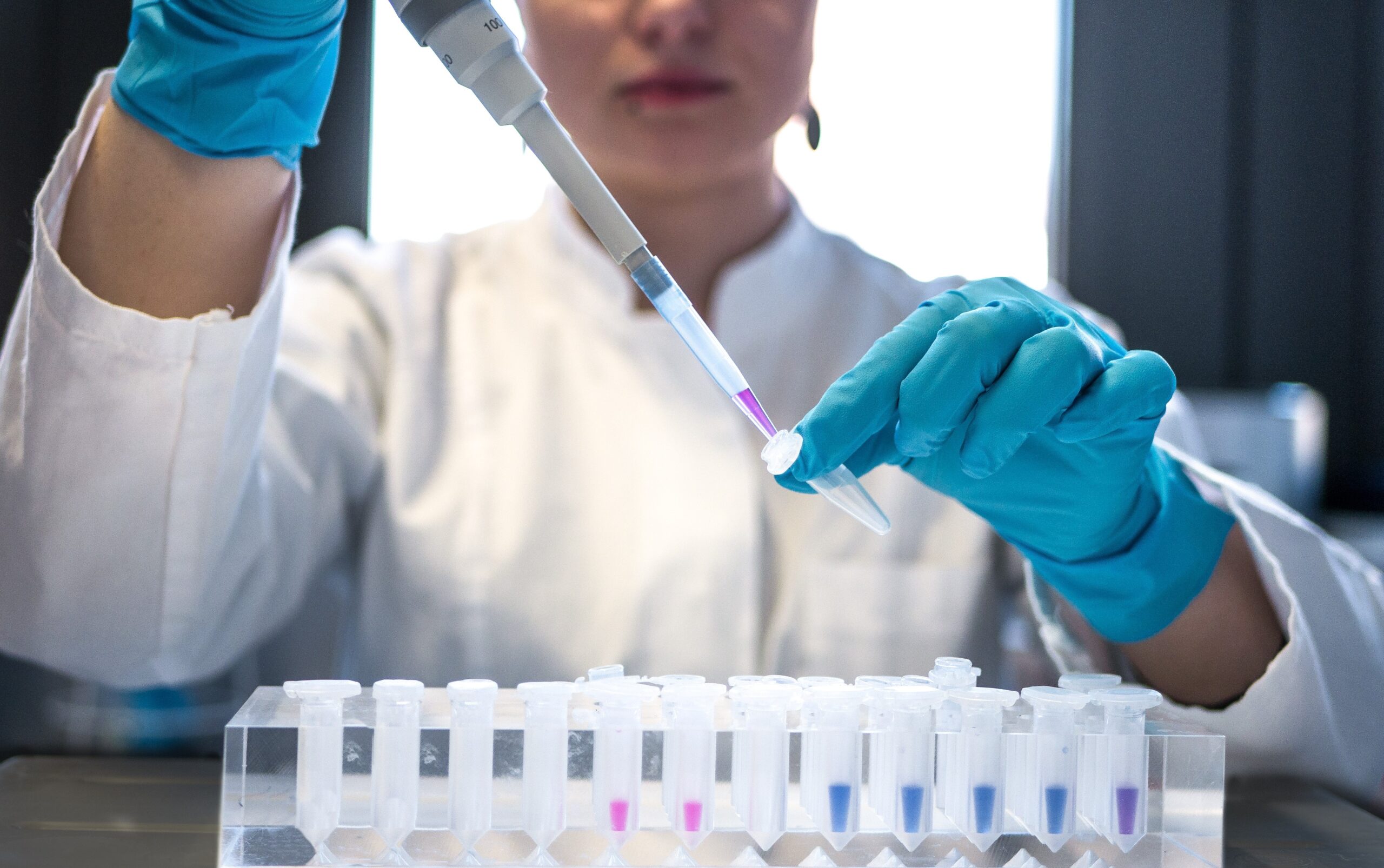

With the charity PSC Support, the leading patient organisation for people living with PSC, LifeArc is funding the FARGO trial led by the University of Birmingham. The trial aims to find out if a treatment called faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) can slow the progression of PSC and improve the quality of life for patients.

FMT involves transferring stools containing natural microbes from the gut of healthy donors, refining it in a lab, and transferring it into the bowel of people with PSC. The treatment could help reverse the imbalance of gut microorganisms.

From idea to patient benefit

Early research has shown that FMT is safe, is effective in treating irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and improves liver blood test results in some people. This latest grant will enable the team to accelerate and scale up their research to answer the key questions that will allow them to take this treatment from idea to benefit patients.

Ashley is optimistic about the prospect of a simple, effective new treatment for PSC that could make a huge difference to people’s lives.

“Instead of surviving, you’d be living – while avoiding the extreme of a liver transplant,” he says. “It would not only benefit people with PSC but also their families. My mum and dad have sacrificed a lot over the years because of my health.”

Working to change clinical practice

PSC Support has a wealth of experience working with medicines regulators on drug development for this condition.

It is hoped that this study will lay the foundation for future work on a larger scale, which may lead to FMT being available across the world. In parallel, PSC Support will work with the wider study team to support delivery of FMT as a treatment after the trial has finished.

This will include submitting trial documents for the UK medicines’ regulatory agency to broaden access to new treatments for people living with the disease.

Find out more about the rare disease projects we fund